Gag clauses were originally incorporated into employment contracts to prevent employees from publicly disclosing information about their employer, workplace or work. In other words, to gag potential whistle blowers.

[Here in Australia, gag clauses appear to be mostly used to conceal gender pay inequity but that’s a whole other blogpost.]

More recently, gag clauses have become popular inclusions in commercial terms and conditions, and contractual agreements, to block consumers from posting negative online reviews. In a ‘seller beware’ marketplace, businesses are using these clauses as a heavy-handed means of online reputation management.

There’s compelling evidence to show gag clauses disempower consumers. The threat of litigation works wonders.

Change may be imminent. In the United States, if passed by Congress, the proposed Consumer Review Freedom Act will limit the ability of businesses to retaliate against customers who express a negative opinion, or to obstruct consumers from sharing their viewpoint.

Yelp and TripAdvisor, among others, advocate the legislation will preserve freedom of speech. Positive, negative or neutral, consumers have the right to have their say without repercussion. Or do they?

Word of mouth is the most powerful form of marketing and the proliferation of social media and user-generated websites (like Yelp and TripAdvisor) mean both the risks and the rewards have increased exponentially.

The American legislation, and the knock on effect it would inevitably have elsewhere, would challenge many businesses.

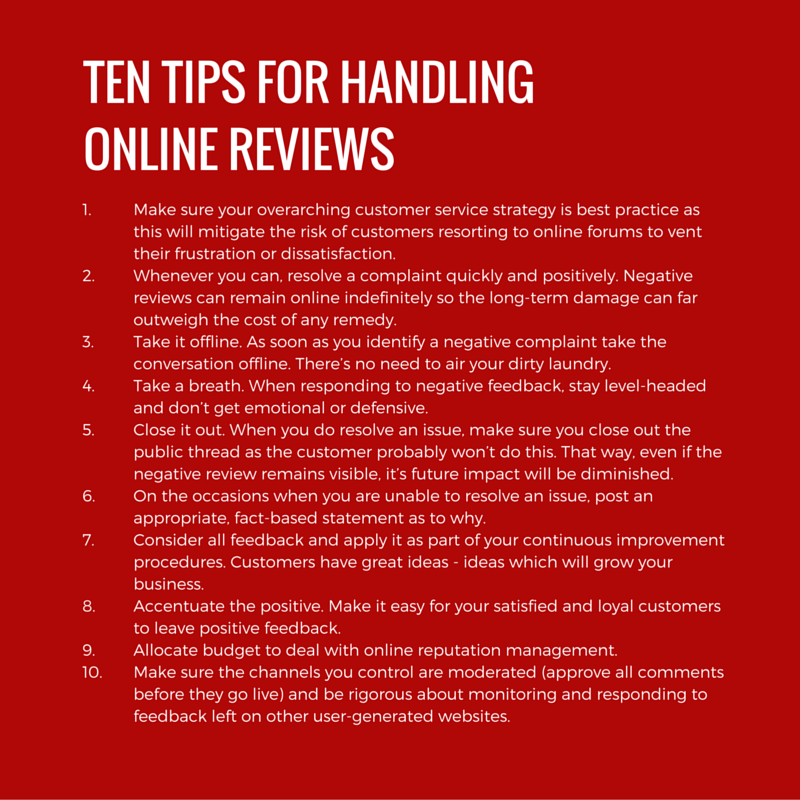

Most companies will have mechanisms in place to control what is posted to their own accounts – their website and social media sites will be carefully monitored, censored and sanitised. In most cases, feedback will be moderated.

In contrast, many user-generated sites allow consumers to post reviews without proof of purchase or validation, and anonymously. That’s akin to laying out a welcome mat for internet trolls and cyber bullies.

A 2015 study by online reputation management firm Igniyte, found bad reviews cost one in five UK companies up to £30,000 (AU$57,000 or US$42,000) to correct. Moreover, half the respondents said they had experienced unfair reviews, or been the victims of malicious reviews or trolls.

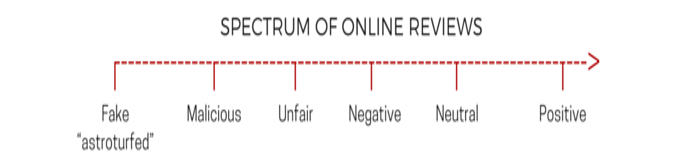

Companies can’t cry foul every time a dissatisfied consumer airs their opinion. There’s a whole spectrum of online reviews (see below) which begs the question: is the consumer being inflammatory, justifiably critical or something in between?

One thing is for sure: giving a voice to consumers will sustain a whole new generation of reputation managers and defamation lawyers.